Showing posts with label Efrem Zimbalist Jr. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Efrem Zimbalist Jr. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 25, 2015

MICHAEL HORSE – FROM TONTO TO DEPUTY HAWKS!

Michael Horse & Klinton Spillbury

More than a year ago I was at the Autry’s Annual

American Indian Marketplace,

where I met artist, actor and musician Michael Horse. He’d starred on David Lynch’s cult TV series

TWIN PEAKS, as Dep. Tommy ‘Hawk’ Hill, but first gained fame playing Tonto in the

infamous THE LEGEND OF THE LONE RANGER (1981).

(That’s the one that caused an uproar before they even rolled camera,

when the producers forced former Lone Ranger Clayton Moore to stop wearing his

mask. They went on to cast virtual non-actor

Klinton Spillsbury as LR, and continued downhill from there.)

While Spillsbury never acted

onscreen again, Michael Horse has had a long, successful acting career on big-screen

and small, worked extensively as a voice actor, a stuntman, and as both a

graphic and jewelry artist. When the

more recent infamous LONE RANGER came out, responding to Johnny Depp’s

headgear, Horse Facebooked a picture of himself with a chicken on his

head. When we met, he was very excited

to have just guested on an episode of HELL ON WHEELS, where he actually wore a

bird on his head.

Michael Horse at the Autry

Time flies! When we did this interview, there was talk of

a possible revival of TWIN PEAKS. Now

the show is in pre-production, and Michael Horse is back as Deputy Hawk.

HENRY: Playing

Tonto is a pretty big way to start an acting career.

MICHAEL: Yuh, went right into a huge movie.

H: Was that your first acting role?

M: No, I did

a couple of MARCUS WELBYs. I was a

musician with Universal Records, and once in a while they’d throw me something,

but I never wanted to be an actor. I

still don’t know if I am. Recently I was

working on something, and the guy goes, “Give me this look.” I go, “Look, I’ve got two looks: I’ve got

this way and this way. I can give ‘em both

to you all day long, but that’s about the extent of what you’re gonna get from

me.” Olivier I ain’t.

H: As a

musician, what do you play?

M: I was a

fiddle and bass player. I did a lot of

bluegrass and rock & roll for years, and just got tired of it. It sounds very glamorous, but you’re doing

these big tours and staying in Holiday

Inn, and we used to travel by bus – and we’re not talking the buses they

have now, we’re talking by bus. It was pretty hard traveling. We didn’t have a lot of electricity when I

was a kid, so everybody played music; we entertained ourselves. When I was growing up everybody in my family

played something. I am an artist; I’m a jeweler, a painter. That’s what I do.

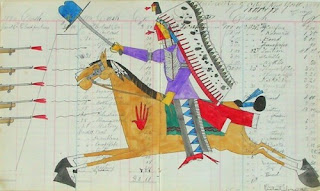

Counting Coup - Ledger Art by Michael Horse

H: I know you

grew up near Tucson.

M: Yes, on

the Yaqui reservation.

H: What was

your childhood like?

M: It was

wonderful. It was hot, not a lot of

amenities. But I went out and played in the

desert. We had goats and horses and

mules. It was nice; it was my

playground. We moved to Los Angeles when

I was about ten. We’d go back and forth. My grandpa had moved there a long time before

us to get a job at Lockheed; they had a relocation program. So I would go back and forth from Arizona to

Los Angeles as a kid. I grew up in the

San Fernando Valley, in the Sunland Tujunga area. My stepdad was an outfitter, took people on

hunting guides. We had a little ranch

there; it was a great place to grow up.

There were bears up there, and you could fish. They built the Hanson Dam. Los Angeles has the biggest urban Indian population

in the United States, especially in the Burbank area. So there were powwows there. I grew up in kind of an inter-tribal

culture. That’s why I know a lot about Plains

people. I grew up with a lot of Lakota,

Cheyenne and Comanche people. I bought

my first house in Topanga Canyon in 1974 for $35,000 bucks cash – it was a

shack, but had an ocean view. I couldn’t

get a p.o. box down there for that kind of money now.

H: What were

you doing when you were asked if you wanted to play Tonto?

M: I was just

renting my art studio from an agent. She

said they’re casting a big movie; they’re doing THE LONE RANGER and looking for

someone to play Tonto. Are you interested? I said no. She said that’s too bad because

they’ll pay a lot of money. And she

quoted a figure at me, and I went, “Oh, Kemosabe!” I looked up (director William) Fraker, and he

had shot some of my favorite films.

H: Not a very

experienced director then, but a great cinematographer – ROSEMARY’S BABY, PAINT

YOUR WAGON, BULLITT, and later TOMBSTONE.

M: I went down to talk to Mr. Fraker; I didn’t think

they’d hire me. I said you send Tonto to

town one time, you’ll have more Indians on your lawn than Custer saw. And Bill Fraker, who I really admired, kind of

talked me into doing it. The only thing,

I said I never wanted to hear the words ‘faithful companion’ ever. But it was a hoot for me. And I had family in New Mexico, and I’d gone to

the Union Art Institute, so we were

filming in my home town, Santa Fe area and around Monument Valley, so it was a

blast. But it was not well-written. And

the casting was really wrong.

H: Klinton

Spillsbury?

M: Yeah, they

knew that (was wrong) right into the picture.

They should have let him go, and got somebody else. James Keach had to dub his whole voice in.

H: The budget

was $18 million, which was a lot of money in 1981. And Lazlo Kovacs did a beautiful job shooting

it.

M:

Beautifully shot, just badly cast and badly written. It was so funny making THE LONE RANGER. I said, I don’t care how much money these

people have. I don’t care where they’re

filming it: we’re going to end up at Vasquez Rocks. And then at the last minute we had to shoot

some stuff out there. That’s where I did

most of my commercials and most of my stunts, most of my horseback stuff, and I

chased so many people around those rocks.

H: Did you

have a sense while it was shooting, did you think it was going to be a hit, or

were you worried?

M: I was just

hoping that I could show my face at a powwow again! (laughs) Please, please get me out of here alive! I mean, I was on the box of Cheerios. I’m thinking, I’m an old American Indian

Movement member. Oh God, what have I

done here? A lot of my friends said

look, you can do some stuff here. I

lobbied for the Indian Child Welfare Bill, I went to D.C., I did a lot of stuff

for both reservation and inner city kids, so it worked out okay for me. I

escaped, and actually had a career from it.

H: And you’re

good in it.

M: I did

okay! They were worried about me,

because I was telling them, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. But (Spillsbury) was so bad he screwed up

before I could do anything wrong. It had

potential, but I think, especially after the Johnny Depp thing, none of us

Indian people ever have to see Tonto again.

I think he’s put away for a long time.

H: A young

man named Patrick Montoya played the young Tonto, but I’ve never seen him in

anything again. Do you know what ever

happened to him?

Sketch by master poster-artist Drew Struzman

M: Oh yeah, I

see him. He lives in Santa Fe, he comes

up once in a while. I think he has a

print shop. They still call him Tonto. It was fun to do. Made some good friends, Mr. Fraker and I

became good friends. Ted Flicker played

Buffalo Bill; we became really good friends.

He created improvisational theatre.

He wrote BARNEY MILLER. He moved

to Santa Fe and became a sculptor. He

would tell me stories about making films in the old days. He and Fraker were friends, so he gave him a

part. And he told Fraker look, this is

not well-written. Why don’t you let me

re-write it? But Fraker didn’t want to

rock the boat. I was lucky to have it,

and lucky to escape from it! (laughs). Not

a very good film. I wasn’t even really

an actor. I just wanted to do okay. But I thought, one day they’re going to do a really

good one, and I’ll be known as the guy who did the crummy one my whole

life.

H: Flash-forward to 2013.

M: And the Creator went, “I’m going to make this one worse than the one you did!” I’m a huge Johnny Depp fan. But something went wrong – I don’t know what

it was. The jokes weren’t funny; the

story wasn’t all that good; the special effects looked all digitized. The Lone Ranger is an icon you don’t really

want to mess with. Just because you want

to make Tonto a more interesting character, you don’t want to dumb down the

Lone Ranger. I think that was a mistake.

H: That’s well

put, and that’s exactly what they did.

They made him foolish, to make Tonto more important.

M: And even

though Jay Silverheels had some of that stilted dialogue, he still was such a

dignified man that it shined through.

You know, that was one of the few real native people we had seen as kids

in the fifties.

H: I was

doing an interview with Dawn Moore, Clayton Moore’s daughter. She was talking about how people forget that

when they started doing THE LONE RANGER series, it was Jay who was the star,

who had been in KEY LARGO and lots of big movies, while Clayton Moore had just been

playing heavies and doing Republic serials.

M: I knew Jay.

I loved him dearly. He had an acting

workshop that was for native people.

That’s how I knew about KEY LARGO and all that stuff. I knew Jay and really liked him. He was in the Motion Picture Hospital when they

said they were going to remake it. He

asked, who’s going to play me? They said

Michael Horse, and he laughed! He

thought that was very funny. Later I met

Mr. Moore – I was at one of the rodeos, and I went up and introduced myself – (this

was) after we had done THE LONE RANGER.

I said, “I’m really sorry, sir, for what they did. You’ll always be the Lone Ranger to me, and

long may you ride.” He said, “How

sweet,” and we had a picture taken together.

I said, how come they didn’t use you? And he said, “Well, I asked them for some

money. I didn’t ask them for an

outrageous amount of money, but look, you’re going to kind of retire me. I want a cameo and I want some money.” And

they just put them out to pasture. He

approached them with this idea. “Look, I’m

getting ready to retire as the Lone Ranger, and I find this kid that’s who’s on

the fence between right and wrong. And

when I think he’s going in the right direction, I’ll turn my back to the

audience, and I’ll hand him the mask.” And

I went, and they didn’t go for that?

They’re idiots: it would have been an iconic, chilling moment!

H:

Absolutely; they needed to make that connection. When I re-ran your movie, there was the role

of the newspaper editor, and I thought it would be a perfect role to give

Clayton Moore as a cameo. And of course

it was John Hart, the man who replaced Clayton Moore for a year on the TV

series when he wanted a raise.

M: Clayton

Moore had been such a role model all those years. Even in the police department, they used to

teach the Lone Ranger rules – you never shoot to kill unless you have to. A lot of those old westerns, when you go back

and look at them, they had a certain ethic to them. They meant well.

Michael Horse with bird headpiece

H: Let’s talk a little about your appearance on HELL

ON WHEELS. About the headpiece, was that

a comment to Johnny Depp?

M: No, it

wasn’t. The lady who did it, she went

through a lot of books on the Comanche.

And there were a lot of people who wore birds: we just didn’t wear them

that big. And when he wears something like that, that’s

a piece of medicine. That’s something to

be respected.

H: You seem very happy to be associated with the

show.

M: Well, it’s so well written, number one; it’s

well-acted, and it’s historically interesting.

The railroads were one of the first of the big corporations that started

pushing everybody around. Especially indigenous people. If you know anything about herd animals, if

you put anything in their way, not just a fence, anything, they’re almost

autistic. The railroad actually changed

the migrations of the buffalo and elk.

And then from the east came this big piece of iron that was smoking and

making noise, and people were killing animals just for the sake of killing. To the Plains people it must have been the

Devil incarnate. I do this kind of

artwork like you saw at the Autry, like the Ledger art. I was painting something from the same week

as The Battle of Little Bighorn. And I

realized from all these periodicals that I read that when that happened, in the

east the Civil War had been over for four years; the Brooklyn Bridge was built;

the first baseball game between Kansas City and Missouri had been played; Edison

was showing the first light-bulb at a symposium. But that’s how wild it still was in Montana

and Wyoming and Colorado. And the Plains

people had no idea what was coming their way.

H: Then it

came, and it was Hell on wheels.

M: And the

Comanche, they were pretty bad boys.

There’s a book out on the Comanches, and I have a lot of Comanche

friends. And I said, “You guys were

pretty bad.” And they said, “Yeah, but

basically we just said, ‘Don’t come here.’”

That’s why the Mexican government allowed a lot of the migration into

Texas: they figured it would be a buffer between them and the Comanche. Some of the finer flight cavalry to ever exist

were the Comanche people. There’s one

piece that I’ve always wanted to do.

They’ve always done Sitting Bull’s story; they’ve done Crazy Horse’s

story. But they haven’t done the story

of Quanah Parker, which is a really interesting piece. I did a one-man play last year, down in

Buffalo Gap, Texas, about Quanah, and he was an amazing man, a person that

lived in two worlds like me, a person of mixed blood, and understood both

worlds, and how they had to come together.

Actually a pretty wise man for the Comanches when they finally decided

to come to the reservation. He made some

pretty interesting deals with the United States government.

H: Yes he

did. It would have helped if the

government had been a little better at keeping those deals.

M: Well, all

governments do that; not just ours. I

liked back in the ‘60s, when all these young people were going, ‘The government

lies,’ and all us indigenous people were saying, ‘No kidding?’

H: News

flash!

M: What an

epiphany that is! The railroads, it made

this country, connected this country.

Ran goods from point to point – that’s what actually made the whole

money-machine of this country work; the railroad. It was a pretty grand scheme. But a lot of times progress rolls over the

people that live on the land. Not just

the indigenous people, but ranchers and farmers. It’s kind of the same thing that’s happening

now, with the energy needs. It’s what

makes the engine run, but it’s kind of screwing up a lot of ranchers and

farmers and indigenous people.

H: Who’d have

guessed they’d all end up on the same side?

M: Yuh, it

happens. And that Swedish villain on

HELL ON WHEELS, that’s one of the greatest villains I’ve ever seen on TV!

H: Oh man,

isn’t he fun!?

M: I met him

recently; he’s a very sweet man.

H: He’s like

a train with no brakes and no tracks – you just don’t know where he’s going!

M: Well, I

imagine there were probably a lot of people like that back then. It was pretty open; you could do pretty much

whatever you wanted to do back then.

H: And of

course, in the Indian Territories, once you got there, there was nothing much

the government could do about it.

M: No. But they gave the railroads a hundred acres

of land on both sides of the (tracks) that they could do whatever they wanted

to with them; they could sell it, they could develop it. It’s really good to see that – like I said, I’m

a big fan of Westerns. I grew up with

Westerns; I think they’re going to come back.

It’s just how they’re written.

But TV’s doing these small, little mini-series, with big stars that

don’t really want to commit to a full series.

Doing nine-episode things like TRUE DETECTIVES was brilliant, it was

really good. FARGO was freakin’

hysterical. Cable’s really allowed for

some really fine television. Last year

they did a seminar at USC about how TWIN PEAKS changed television. And what it did was, it showed people that

anything was possible on television. It

opened all kinds of doors, and changed formats.

It had pretty-much been a formula kind of thing until that went, and

people went, ‘Oh, you can do anything.’

H: I think

all of the miniseries, and shows like HELL ON WHEELS, which they don’t call a

miniseries, but it’s a continuing story; none of them would have happened, none

of them would have been the same without David Lynch being ahead of them.

M: He opened

that door, and said there’s huge audiences for different things. It’s really funny; there’s a lot of young

kids who are seeing it now on the internet.

So it’s more popular than it ever was.

We live in the Berkeley area, and I’ll be going to the movies, and my

wife goes, “Those kids are following you.”

Usually young film students. I’ll

go, “Can I help you?” They’ll go, “Are

you Deputy Hawk?” “Yuh.” And then they go crazy. My wife thinks it’s hysterical.

H: What was David

Lynch like to work with?

As Deputy Hawk

M: David is

the sweetest man, such a sweet man. He’s

like Jimmy Stewart with Salvador Dali’s intestines. He’ll go, “That was really keen, whatcha did! But this time, could you get naked, and bark

like a dog?” David is an artist. Both as an indigenous activist, a native

activist, and as an actor you don’t get a chance to do art in television that

often; and TWIN PEAKS was art. And that

was a wonderful native character. It got

rid of stereotypes, and held some mirrors up to the others, you know. I’m still looking. I’ve been turning down a bunch of stuff, but there’s

a couple of scripts out there that I’m getting ready to do. And I’ve been doing all these student films. It’s nice in my career that I can afford to

do this. These film students will get in

touch with my wife. I don’t get on the

internet – I’m such a Luddite, I just learned there’s a redial button on my

phone. My wife’ll go, “This film student

is looking for you.” They won’t go to my

agent, because he won’t return their call, because they don’t have any money. I’ve done three or four of these little films

for these kids. And it reminds me that

filmmaking is art. It’s been very nice.

H: I know you

did some stunt work.

M: I used to

be around horses. I did a little stint

at rodeo riding; wasn’t very good at it.

The first time somebody paid me to fall off a horse I said, “I can do

that!” Staying on’s the hard part. Then we started the Native American Stunt

Association. We didn’t get the work we thought we were gonna get. I dabbled in it, did a lot of fight stuff,

and it was fun. Did some stuff in

PASSENGER 57 with Wesley Snipes.

H: You acted

in a few WALKER, TEXAS RANGERS.

M: And God bless Chuck (Norris), I love him, I knew

him for years, and friends ask why do you WALKER? I said it’s so bad, I can’t suck. But there are some wonderful scripts out

there. Some guy sent me a script from

Washington State about a little native kid in the 1950s who worships Elvis, and

wants to win a talent contest. It is so

sweet and so well done I told them I’d do it for free. But working on HELL ON WHEELS, that’s a class

act. The series I did in Canada, it was

on for seven years, I did three years of it, called NORTH OF 60. It was strictly for Canadian television. It was so well done, so well written – some

of it written by native people, directed by native people. It had all these great native actors, Gordon

Tootoosis, Tantoo Cardinal, and Graham Greene.

I was one of only two Indian people from the States ever to be on

it. It was a joy to do. It was contemporary, about people who live

way above the 60 parallel. I play a

therapist and a bush pilot. I’m hoping

to squeeze out a couple of things before I retire. I’ve done three or four of these little

sci-fi films, but I’m not going to do anymore because it’s the same thing. My wife laughs, the last one, “You’re the

holy man, you’re inside by the fire, with these two beautiful girls bringing

you food.” I go, “Yeah, I’m not going

outside – the monster’s outside!”

H: In 1982

you were the star of THE AVENGING, and I’m sorry it’s not better known, because

it’s a very impressive independent film.

How did this project come about?

M: They just

got in touch with me, I said send me the script. It wasn’t a lot of money, and I’d just

finished the LONE RANGER, and I said I’d do it, I like this.

H: And you

got to work with Ephrem Zimbalist Jr.

M: Yeah, we

became pretty tight too. I love working

with these old guys, and make them tell me stories. Wranglers are the best – they’ll tell you

everything. My favorite thing to do is I

do cartoon voices. It’s all those people

who used to make gas-noises and got sent to the principal’s office. It’s all old stand-up comics, and guys who

used to have imaginary friends.

H: What is

your favorite of the voices you’ve done?

M: It’s

probably SPIRIT: STALLION OF THE CIMARRON (2002), the horse. I’m fifty voices in that, even the old Indian

woman; she didn’t show up. “I’ll do my

very best.” I’m such a fan of

animation. And usually you record and

then they do the animation. But we were

watching them as they were making it, so there were drawings that moved, and

half-painted things. It’s almost a

classic old Disney kind of piece. There

was a series I did for a while called COWBOYS OF MOO MESA. I played this buffalo called J.R. He was a Rube Goldberg kind of guy; he used

to make all these inventions. I just

loved him.

H: In 1990 you starred in BORDER SHOOTOUT for Ted

Turner’s TURNER PRODUCTIONS. It’s

adapted from an Elmore Leonard novel.

M: That was

fun too. Elmore Leonard – I didn’t

realize until the last five years that he wrote HOMBRE, one of my favorite

movies. Just (Paul) Newman sitting in

the bar listening to those two rednecks hassling those two native guys. Him and Richard Boone, just amazing. That was an interesting little film. And working with Glenn Ford.

H: On his

last Western, too.

M: It took

him a little while to get ready. One of

these young kids was complaining. We’re

working in the middle of the night, and it’s freezing. Finally they get him outside and the kid

said, “You had me waiting outside for him!”

And I said, “It’s Glenn Ford. I’ll

wait as long as it takes.”

H: What was

he like to work with?

M: I was in

awe. I liked the character actors,

too. I used to go to the Beverly Garland

Hotel, have breakfast with Monte Hale, and he would tell me stories about the

old days. Same with the old

fiddle-players. I’d say, I’ll buy all

your drinks, just tell me about the old days – I’m fascinated by it.

H: In BORDER SHOOTOUT, you also worked with Michael

Ansara. Although he was from Syria, he

spent much of his career playing American Indians. A number of non-Indian actors have

specialized in Indian roles – in addition to Ansara, X. Brands and Iron Eyes

Cody.

M: A lot of them.

Ricardo Montalban, Sal Mineo.

H: Any problems with that?

M: You know,

the process of acting is to portray something that you’re not. But if you’re doing a cultural piece, and you

don’t bring somebody who comes with that culture, you’re going to cheat

yourself. I’ve talked to casting people,

and they’ll say, we’ve seen a hundred guys, and they’re not doing what we want

them to do. And I said, if you’ve seen a

hundred Indian guys, and they’re not doing this, maybe they don’t do that. Will Sampson was more interesting just

standing there, not saying anything, than all the non-native actors that ever

played anybody. And there were

exceptions. Paul Newman nailed it. Charles Bronson used to come pretty

close. A really good actor can do

it. But the native guys, the full-blood

guys don’t get a chance to play anything else.

But it’s changing. Digital film

has put it back in the hands of filmmakers.

There are a lot of native filmmakers that are making films out

there. And they don’t need Hollywood,

they don’t need big money, they don’t need the big stars. And there are wonderful, wonderful films.

H: What’s

your favorite film?

M: LITTLE BIG

MAN. That was the first time I saw one of

those funny old elders that I grew up with (on the screen). Those little people are just so funny, and

Chief Dan George was just magic. “Am I

still in this world?” “Yes, grandpa.” “Ahhh!”

Dustin Hoffman tells him, “I have a white wife.” “Does she show enthusiasm when you mount

her?”

I really know how you make a bad

movie, but I’m really trying to figure out how you make a good movie.

THAT’S A WRAP!

Just one topic this week, so I hope you enjoyed

it!

Happy Trails,

Henry

All Original Contents Copyright August 2015 by Henry

C. Parke – All Rights Reserved

Monday, May 5, 2014

CLASSIC MOMS AT ‘THE CABLE SHOW’ PLUS ‘WITH BUFFALO BILL’ REVIEWED!

MEETING CLASSIC MOMS – AND MORE – AT

‘THE CABLE SHOW’

From Tuesday, April 29th

through Thursday, May 1st, thousands of people in all aspects of the

cable television industry converged on the Los Angeles Convention Center for The Cable Show. Over 200 exhibitors filled the exhibit hall

promoting their channels, services, hardware, software and other products. I was the guest of INSP, the channel famous

for their daily TV westerns and Saddle-Up

Saturday block, and their exclusive airings of THE VIRGINIAN and HIGH

CHAPARRAL.

INSP had arranged to have a pair of

stars from two of their most popular series, two of America’s favorite moms,

Karen Grassle from LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE, and Michael Learned from THE

WALTONS, present to meet-and-greet and pose for pictures. Knowing how long it had been since they’d

starred in their series – LITTLE HOUSE had their last season in 1983, and THE

WALTONS in 1981 – I was delighted to find how charming and vivacious both

ladies were. When I took my turn posing

with them, I commented that I was excited to meet them because I’d enjoyed

their shows so much, and also because they’d both starred in episodes of

GUNSMOKE, something neither one knew about the other. “I played a whore!” Karen blurted out.

“I played a whore, too!” Michael

Learned added with a laugh. I was

delighted to be able to discuss their experiences in Dodge City.

Karen Grassle in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE

KAREN GRASSLE: Well, I came at the very tail end of

GUNSMOKE, right after we did the pilot for LITTLE HOUSE. Victor French, who played Mr. Edwards (on

LITTLE HOUSE) was going to direct his first television episode ever (THE

WIVING, 1974). And so he wanted me to come

on, and I went on, and I was one of a number of saloon girls. And at that time I was a big feminist, and I

had hair under my arms! (Laughs) And so they had to come very politely to me

and say, ‘Miss Grassle, do you mind?’ I

said of course – that was pretty funny.

We did a show where these boys, who were kind of…missing a few

batteries, they were told by their dad, ‘Go find wives, or you’re not going to

get any inheritance!’ So they went to

town and kidnapped a few saloon girls; brought us out to the farm. It turned out that the farm where we shot

became the location for THE LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE.

MICHAEL LEARNED: That’s a really great story.

HENRY: Now Miss Learned, you did two GUNSMOKE

episodes and a movie.

MICHAEL LEARNED: Well, in the first one (A GAME OF DEATH…AN

ACT OF LOVE, part 2 1973) I played a lady of ill repute in a court scene. I was a witness, and I only remember because I

saw it recently on Youtube. It was very

early (in THE WALTONS run), and they had to clear me; there’s a morals clause

when you sign a contract to do a series – I don’t know if you had to sign one,

Karen, but I did. So they had to get

clearance from (WALTON’S creator) Earl Hamner and (producer) Lee Rich and Lorimar, and they let me do it. Then I did something called FOR THE LOVE OF

MIKE (later retitled MATT’S LOVE STORY 1973).

Matt’s had a concussion, and he’s lost his memory. We fall in love, and I’m the only woman that

Matt Dillon ever kissed. And out of that

kiss…came a little baby! (laughs)

HENRY: It must have been a great kiss.

MICHAEL LEARNED: It was, actually. He called me up and asked me out for a

date. I thought he was a really great

guy, and I like him a lot. Very

self-effacing and kind. I was kind of

nervous; (to Karen) like you, I was just starting out. Then they did follow that up with a

move-of-the-week (GUNSMOKE: THE LAST APACHE – 1990), where he doesn’t know he

has a child, because he gets his memory back, and he goes back to Miss Kitty,

where he should have been in the first place.

HENRY: And he never kissed her.

MICHAEL LEARNED: He never kissed her – not on screen

anyway. So in the movie-of-the-week, our

child is abducted. And I call on him to

find her, to bring her back. And he discovers

that he has a child that he didn’t know he had.

And that’s my history with GUNSMOKE.

And the funny thing is that I never told him, but when I was a child, I

used to watch GUNSMOKE with my dad. And

so the first time I did the show with him, I couldn’t speak, I was so shy. I just sat there looking at him. But he warmed me up; he was a very nice

guy.

HENRY: Now Karen, you also did WYATT EARP with Kevin

Costner. What was that experience like?

Karen Grassle relaxing

KAREN GRASSLE: That was a lot of fun. I was living in New Mexico at the time, and

they came there to shoot. They had done

some casting in L.A. Then they tried to

fill out some of the roles in Santa Fe. I

was teaching at the time, at the College of Santa Fe, teaching acting for the

camera. There was a great studio there;

that’s why they were there. And so I got

to do this little part, as the mother of Kevin Costner’s bride. And I worked with some great people: Gene

Hackman, Kevin of course – he was amazing.

Gene Hackman was so terrific. And

then the camera would cut, and he was, ‘Well, that wasn’t any good.’ You know, we’re so self-critical,

actors. It was a lot of fun.

HENRY: What is WALTONS creator Earl Hamner like?

MICHAEL LEARNED: He’s just one of the greatest guys in the

world. Sweet, kind, and everything you

think he would be. He’s got a raunchy

sense of humor, which saves the day; otherwise you’d get diabetes. He likes to drink; he’s just a great

all-around guy. He and his wife have been together for I don’t know how many

years; theirs is a real love story. I think

somebody’s trying to do a documentary on him, but somebody should do a story

about their love story. Recently I

talked to him, and he said, “My wife is at the beach for the weekend, and I’m

just sitting around crying, I miss her so much.” So sweet, after all those years – sixty, I think.

Incidentally, Ralph Waite, who

played John Walton Sr. opposite Michael Learned, died this past February at the

age of 85. Active until the end, in 2013

he was playing continuing characters in BONES, NCIS, and between 2009 and 2013,

he did 94 episodes of DAYS OF OUR LIVES.

One of his last performances was in a dramatic short for INSP called OLD

HENRY. You can see the entire 21-minute

film HERE.

Visiting exhibits of other

channels, I learned what is on the horizon for Western fans, and discerning viewers

in general. The STARZ/ENCORE folks told

me that the highest viewership of any of their many channels, right after

STARZ, is ENCORE WESTERNS. At present

they don’t have plans to create any original Western programming.

At HALLMARK CHANNEL and HALLMARK

MOVIE CHANNEL, WHEN CALLS THE HEART, the Western Canadian romance series, has

ended its first season, and cameras have already rolled on season two. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the two HALLMARK

channels have announced a slate of about thirty TV movies, and not one is a

Western. This would not be a surprise

with any other network, but HALLMARK has staunchly supported the genre when no

one else did, and averaged at least two Westerns per year. The popular GOODNIGHT FOR JUSTICE franchise

produced three features starring and co-produced by Luke Perry, and last year’s

QUEEN OF HEARTS is by far the best of the group. As of now, there are no plans to make

more. HALLMARK has decided to shift its

focus to mysteries, and in fact, the HALLMARK MOVIE CHANNEL will be re-branded

THE HALLMARK MYSTERY CHANNEL in October.

For those of us who worry that

younger viewers aren’t discovering classic films, some heartening news:

according to TCM, two thirds of their 62 million viewers are between the ages

of 18 and 49.

AMC is in the middle of its first

season of TURN, the Revolutionary War spy series, and this summer will be

bringing back HELL ON WHEELS for its fourth season.

THE HISTORY CHANNEL will soon be

presenting its own Revolutionary War series, SONS OF LIBERTY, focusing on such

characters as John Adams, Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Benedict

Arnold.

A&E will deliver a new season

of LONGMIRE starting on June 2nd, and FX will bring us one more

season of JUSTIFIED, but then they’re pulling the plug. Over the last couple of years, the Round-up

has been following a number of proposed series at all the major networks, and

some pilots have been shot, but not one, Disney’s BIG THUNDER prominent among

them, has gotten a go-ahead.

At the seminars that I attended,

and in talking to many of the exhibitors, the main topic of conversation, of

concern, was making TV content easily and instantly available on all possible

devices. This is absolutely sensible;

this is their livelihood. And yet, as an

outsider, it seems to me that such content is too available already. Just

a few years ago, any group of people standing around waiting, at a post office

or bank or about to board a plane, would feature a substantial number of people

reading newspapers or books, or doing crossword puzzles, or talking to each

other. The reading and conversation was

gradually replaced by people talking loudly in their cell phones, and kids with

annoying loud portable video games – the same kids who have wheels on the

bottom of their sneakers. Now nobody reads

or talks at all; they text, or they stare at videos on their iPhone and check

Tweets – reading Tweets is not actual

reading. At a high school last week, I

observed a class waiting for a late teacher : I counted sixteen kids sitting on

the floor, side by side, none talking, none acknowledging each other, all

staring at their smartphones. They were

waiting for a drama class to begin, and not one was communicating with

another. And for all the constant

updating, if you can pry a minute or two of conversation out of them, you will

find only a tiny percentage has any idea of what is going on in the world. They don’t need to have watching TV any

easier. They need to watch less, read

more, listen more, and then talk more.

WITH BUFFALO BILL ON THE U.P. TRAIL – A Video Review

This newest silent Western release from Grapevine Video was made in 1926 by

Sunset Productions, just a year before sound would turn the movie industry

upside down. One of the particularly

appealing aspects of the film is that paralleling the coming changes to the

movie industry are the progress-borne changes in the lives of Buffalo Bill Cody

and other characters. The U. P. in the

title is the Union Pacific Railroad, and the film concerns a time when the Pony

Express, once Cody’s employer, is disappearing, and the wagon train is soon to

be replaced by the transcontinental railroad.

Just as the specificity of the time is unusual, so

are many of the characters and plot elements.

In a surprisingly plot-heavy opening, we are quickly introduced to Cody,

an Indian whom Cody rescues and befriends (played by actual Indian Felix

Whitefeather), a wagon train whose passengers include a runaway wife and her

paramour, and a runaway slave (played by apparent white guy Eddie Harris). They are pursued by a lawman, and a parson,

who happens to be the abandoned husband of the runaway wife.

The wagon train reaches the fort, and soon Cody and

a friend, seeing the coming of the rails as inevitable, become land speculators. Reasoning

that the rails must go through a certain pass, Cody and company commence to

build a town along the route, but are soon up against the railroad’s corrupt

head surveyor, who says he will either be made an equal partner in the town, or

he’ll find another route, regardless of what it costs the railroad.

There’s a good deal of action here, much of it

involving the Indians, and a purposely stampeded herd of buffalo. There are even more subplots – the Major, his

daughter and her suitor; the crooked gambler devoted to his beautiful little

daughter – and all of them are paid by the end: surprising in a 53 minute

film. One of the curious effects of so

much happening is that Cody is only nominally the lead – much time is devoted

to other characters.

Portraying Buffalo Bill Cody, star Roy Stewart is

not a familiar name today, but he was a big star in silent films, co-starring

with Mary Pickford in SPARROWS that same year.

Most of his roles were in Westerns, and when sound came in, he was

gradually relegated to bit parts, often unbilled, but he managed to compile

nearly 140 film appearances. He’s big

and likable and good with the camera. He

makes an acceptable Buffalo Bill Cody, especially once he starts wearing the

familiar fringed buckskin jacket. The

one odd choice was keeping the long brown hair, but not the mustache and

goatee. To look right as Cody, you have

to go full hair-and-whiskers, ala Joel McCrea, or abandon the fuzz entirely,

ala Charlton Heston. The hair alone

triggers distracting comparisons to Barrymore’s MR. HYDE, and Tiny Tim.

The movie is well-acted and entertaining, and some

elements of the story are very progressive for their time. The first sighting of Indians is preceded by

this title-card: ‘The scouts of the original Americans kept watchful eyes on

all white invaders.’ Contrast this with

the words from the original poster: ‘DO YOU LIKE

ACTION AND HAIR-RAISING THRILLS? You will see Indians attacking the whites ---

Indian warfare in all its horrors - action - fights - and the most thrilling

suspense you have ever witnessed!’

Obviously not the same writer.

Also progressive, in spite of the

white actor portrayal, and some standard-for-the-time toadying, is the runaway

slave. When he is discovered, not even

the lowest characters in the story ever consider returning him to his

owners. The film is well directed,

handsomely shot and generally well-edited – though a herd-of-buffalo shot that

does not match the action is featured much too often – and the print, though

scratchy in places, is quite crisp and clear, with sharp lines, dark blacks, and

a wide range of grays. Priced at $12.99,

with a piano score by David Knudston, it is available from Grapevine Video, which has about 600 films currently available, and

frequently brings out more. THIS LINK

will take you to the WITH BUFFALO BILL page.

CATCH ‘THE LONG RIDERS’ SAT. MAY 10 AT THE AUTRY!

Walter Hill’s 1980 film about outlaw families has an

irresistible gimmick: brother outlaws were played by actual brothers. Thus the Youngers are portrayed by David,

Keith and Robert Carradine (their father John had scenes, sadly deleted), the

Millers by Dennis and Randy Quaid, the

miserable Ford brothers by Christopher and Nicholas Guest, and the James boys

by James and Stacy Keach, who also co-wrote the script with Bill Bryden and

Steven Smith. I haven’t seen it in

years, but I remember it as very entertaining, with memorable action

scenes.

Presented as part of the Autry’s ongoing monthly ‘What

is a Western?’ series, it will be preceded by a discussion lead by Jeffrey

Richardson, Gamble Curator of Western History, Popular Culture, and Firearms.

EFREM ZIMBALIST JR. DIES AT 95

The Round-up is sorry to note the passing of actor

Efrem Zimbalist Jr. The son of concert

violinist Efrem Zimbalist Sr. and opera star Alma Gluck, he was awarded a

Purple Heart for his military service, and first garnered wide attention playing

private eye Stu Bailey on the Warner Brothers 1960s detective series 77 SUNSET

STRIP. He later starred in about 250

episodes of THE F.B.I. Though not

particularly known for Western roles – his easy sophistication made him more

natural in big city stories – he did appear early in his career in the Civil

War drama BAND OF ANGELS, with Clark Gable.

And in his SUNSET STRIP days he did all of the WB westerns series: five

MAVERICKS, and one each of BRONCO, SUGARFOOT, plus a RAWHIDE, and in 1982

played Michael Horse’s father in the impressive and often overlooked THE

AVENGING. In the frst season of the 1990s

ZORRO series he played Zorro’s father Don Alejandro de la Vega, before handing

the role over to Henry Darrow. A busy

voice actor late in his career, Zimbalist was the voice of Batman’s butler,

Alfred, in a half dozen series. Among

his finest work was playing L.A. Police Sgt. Harry Hansen in the only good

movie on the subject, WHO IS THE BLACK DAHLIA? starring Lucie Arnaz.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY ANN-MARGRET

Norman Rockwell's portrait of Ann-Margret

for STAGECOACH

I’m a little late, but happy birthday to Ann-Margret,

whose birthday was April 28th.

In 1966 she starred in the remake of STAGECOACH, playing Claire Trevor’s

role of Dallas, opposite Alex Cord in John Wayne’s role of The Ringo Kid. Seven years later she was starring opposite

the real Duke in Burt Kennedy’s THE TRAIN ROBBERS. Then in 1994 she played Belle Watling in the

miniseries sequel to GONE WITH THE WIND, SCARLETT.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY WILLIE NELSON

Willie in BARABOSA

Born on April 30th, 1933, Willie has

continued the tradition of the singing cowboy started by Gene Autry, but has

done it in his own way. Starting in THE

ELECTRIC HORSEMAN in 1979, Willie has appeared in many westerns, often as the

lead, sometimes as a cameo. Among them

are BARABOSA, THE LAST DAYS OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES, STAGECOACH, REDHEADED

STRANGER, ONCE UPON A TEXAS TRAIN, WHERE THE HELL’S THAT GOLD?, and several DR.

QUINN episodes. And though it’s been

often said that, with his chinful of whiskers, he could save studios money by

being his own sidekick, there’s something about him, perhaps his voice, that

makes ladies respond in a way that few ever did for Al St. John, or even Gabby

Hayes.

THAT’S A WRAP!

Next week I’ll definitely finish up my coverage of

the TCM Festival, and either the WILD BUNCH LUNCH at the Autry, or THE SANTA

CLARITA COWBOY FESTIVAL at Gene’s Melody Ranch.

Have a great week!

Happy Trails,

Henry

All Original Material Copyright May 2014 by Henry C.

Parke – All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)