Showing posts with label Linda Cristal. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Linda Cristal. Show all posts

Sunday, May 11, 2014

VOTE FOR MOTHER(S) OF ALL WESTERNS, PLUS TARANTINO DROPS SUIT, ‘SOME GAVE ALL’ REVIEWED, ‘LONG RIDERS’ INSIGHTS!

VOTE FOR THE MOTHER(S) OF ALL WESTERNS!

Karen Grassle in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE

The Round-up wants to honor the Best Moms’ of

Western film and TV. Please post your choices

under comments or send an email -- and your suggestions for great ladies I’ve

left out. And please SHARE this, so we

can get more voters!

FOR BEST MOTHER IN A WESTERN MOVIE, the nominees

are: Maureen O’Hara in RIO GRANDE, Jean Arthur in SHANE, Jane Darwell in JESS

JAMES, Katie Jurado in BROKEN LANCE, Dorothy McGuire in OLD YELLER, Cate

Blanchett in THE MISSING.

Dorothy McGuire in OLD YELLER

FOR BEST MOTHER IN A WESTERN SERIES, the nominees

are: Barbara Stanwyck in THE BIG VALLEY, Linda Cristal in THE HIGH CHAPARRAL, Karen

Grassle in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE, and Jane Seymour in DR. QUINN, MEDICINE

WOMAN.

Granted, we’d have a lot more to choose from if we

were going for ‘Best Saloon Girls,’ but after all, today isn’t Miss Kitty’s

birthday, it’s Mother’s Day. And here

are the Honorary Mothers Day awards:

BEST MOTHER IN A MOVIE IF SHE’D LIVED – Mildred

Natwick in THE THREE GODFATHERS.

BEST MOTHER WHO NEVER TOLD THE FATHER THAT THEY HAD

A CHILD – Miss Michael Learned, who was impregnated by amnesiac Matt Dillon

(not the actor Matt Dillon, but James

Arness), in GUNSMOKE – THE LAST APACHE.

BEST MOTHER YOU HEARD ABOUT BUT NEVER SAW – Mark

McCain’s mother in THE RIFLEMAN.

BEST STEPMOTHER EVER, IF THE KIDS HAD LIVED –

Claudia Cardinale in ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST.

TARANTINO DROPS ‘HATEFUL 8’ LAWSUIT AGAINST GAWKER

According to Deadline: Hollywood, writer-director

Quentin Tarantino has dropped his copyright infringement suit against the

website Gawker, for posting his Western work-in-progress screenplay THE HATEFUL

EIGHT online. He has withdrawn his suit ‘without

prejudice,’ which is legalese for saying he reserves the right to refile at a

later date.

For those who haven’t been following the case,

Tarantino, frustrated at how quickly his scripts have been leaked, went to

great lengths to make sure this one would not be. When one of the only three copies to leave

his hand turned up on the internet, he cancelled the project, and filed

suit. As the case moved along on the

docket, Tarantino decided, as a fund-raiser for the L.A. County Museum of Art,

to hold an on-stage script reading of the script, which was held on April1 9th. You can read Andrew Ferrell’s review of the

event for the Round-up HERE .

As had been hoped by many of us, the days of

rehearsal reignited Tarantino’s enthusiasm for the project, and he is now

engaged in writing another draft. Apparently

the largest legal hurdle Tarantino’s lawyer’s would have faced would be the

fact that Gawker did not post the purloined script on their site, but rather

posted a link to where it could be found on someone else’s site. In a way it is disappointing that the case is

not going forward, as it would be useful to have the law clarified. While I cannot deny having downloaded scripts

from the internet, posted by people who often had no authority to put them

there, the difference is that they were scripts from completed and released

movies: there were no secrets exposed.

But it’s clearly good news that Tarantino is focusing on the re-write

rather than problems encountered with the first draft.

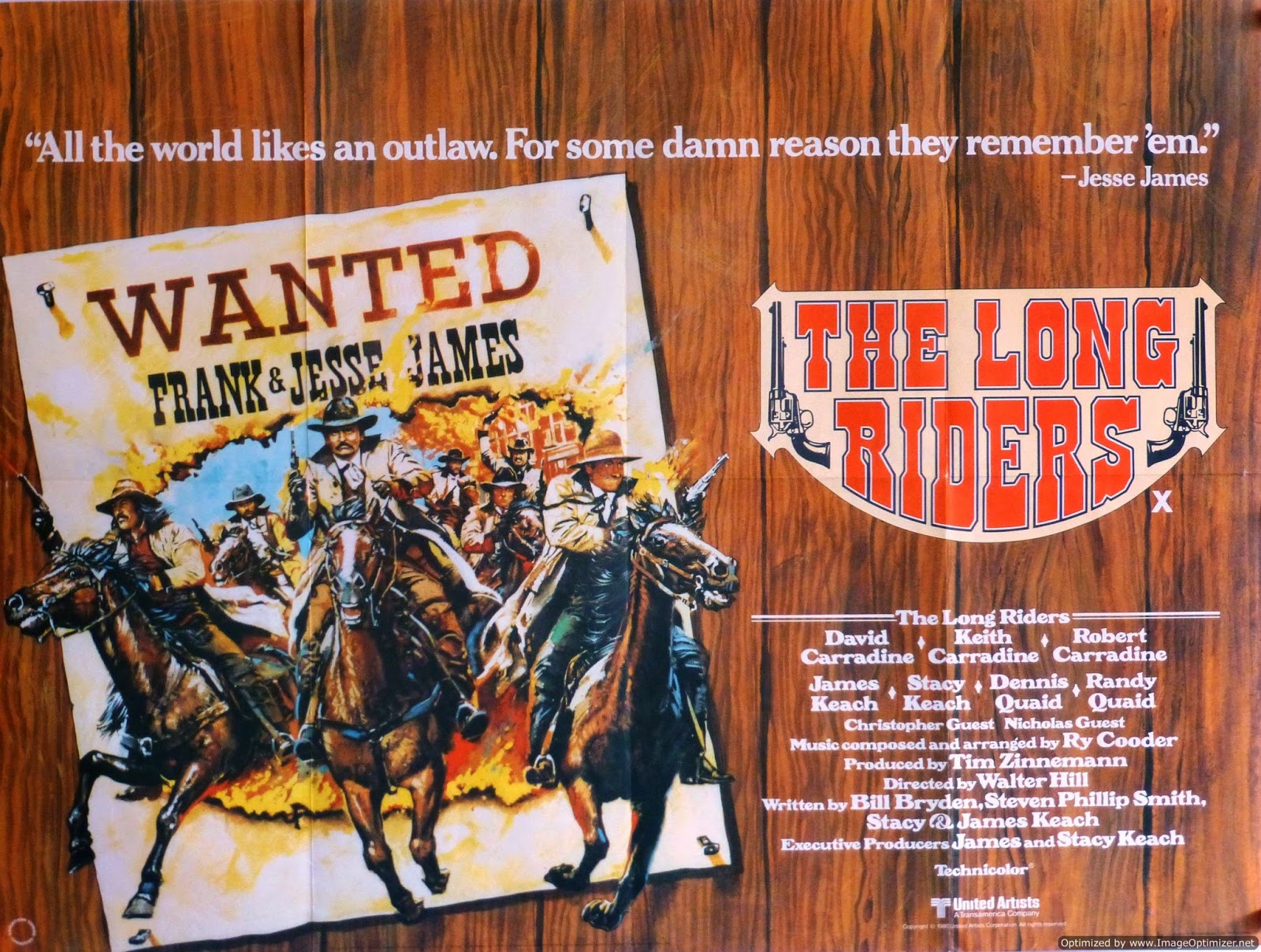

AUDIO INSIGHTS FROM ‘THE LONG RIDERS’ AT THE AUTRY

I hadn’t seen this Walter Hill-directed film on a

screen since its 1980 release, and it holds up wonderfully. The trick to this one was casting actor

brothers as outlaw brothers: the Youngers are played by David, Keith and Robert

Carradine; Frank and Jesse James are Stacy and James Keach; the Miller brothers

are Dennis and Randy Quaid; and the dirty little coward Fords are Christopher

and Nicholas Guest. Also of note in the

cast are Pamela Reed as Belle Starr, a very young James Remar as Sam Starr, and

a great cameo by Harry Carey Jr. as a stagecoach driver held up by the

Youngers.

As always, Curator Jeffrey Richardson’s introduction

was full of information I’d never heard before.

For instance, the genesis of the project was a 1971 PBS docu-drama about

the Wright brothers, which starred the Keach brothers as Orville and

Wilbur. They had such fun working

together that they started looking for another project to do together. Reasoning that they’d enjoyed the ‘Right’

brothers, they decided to play the ‘Wrong’ brothers, Frank and Jesse. This led to the stage musical, THE BANDIT

KINGS, and they decided to try and make it into a film.

The film musical never happened, but they kept

trying, and came up with the idea of casting all brothers. Potential director George Roy Hill blew it

off as too gimmicky. Then in 1975, James

Keach was playing Jim McCoy in a TV movie, THE HATFIELDS AND THE MCCOYS,

starring Jack Palance as Devil Anse Hatfield.

Robert Carradine was playing Bob Hatfield, and wanted to know from Keach

about the project. Pretty soon it

started looking real, and Beau and Jeff Bridges were soon onboard, though

schedule conflicts would cause them to be replaced by the Quaids.

Randy Quaid, Keith Carradine, Stacy Keach

Jeffrey had a surprise guest in LONG RIDER

supervising sound editor Gordon Ecker.

The work of a sound editor is much more covert than that of a film

editor, and he revealed some fascinating details about how the soundtracks were

built. At Walter Hill’s direction, a

slightly different gun-sound was developed for each star – they may all have

been firing Winchester rifles, for instance, but no two sounded quite alike.

Hill liked to underplay the audio volume in the

non-action scenes, so the LOUD action would really jump out at you. Foley sound is the recording of live effects

synchronized to picture, and to make the horse foot-falls sharper than the

usual cocoa-nut shell method, they attached a Lavalier (clip-on) microphone

onto a boot’s instep and stamped it in the dirt.

My favorite revelation was about the use of gunshots

as a premonition. There were many shots

fired for every hit. For the gunshots

where characters actually got hit, a ricochet effect was used. Now, as Ecker pointed out, normally a

ricochet sound would only be used if the bullet bounced off of something, as

opposed to hitting someone. But what they

did instead was play the ricochet sound in

reverse before the shot, then the shot, followed by the ricochet played

forward. The unconscious psychological

effect is that, amidst all the others shots, you begin to anticipate, like a

premonition, the bullets that will hit a victim, a fraction of a second before

it happens. It’s an unnerving effect. I hope to have a full interview with Mr.

Ecker in the near future.

If I were booking film programs, I would love to run

THE LONG RIDERS and TOMBSTONE as a double-feature – the two great Westerns

about brothers, on each side of the law.

SOME GAVE ALL by J.R. SANDERS – A Book Review

SOME GAVE ALL – Forgotten Old West Lawmen Who Died

With Their Boots On, is a remarkable piece of research and writing by J.R.

Sanders, who has previously penned two books, and many articles for WILD WEST

magazine. His fascination with the wild

west goes back to his youth, growing up in the once lawless cattle town of

Newton, Kansas, and childhood vacation visits to Abilene, Dodge City, and the

Dalton Gang’s hideout.

As a former Southern California Police Officer, he

takes the subject of his newest book seriously and personally. He sifted through many possible lawmen to

focus on, and selected ten to report on in depth. In all likelihood, not even one will be

familiar to the reader. And that’s part

of the point: plenty has been written about the Earps and the Mastersons, and

these ten heroic men have been too quickly forgotten, some seemingly before

their bodies had gone cold. The fate of some

of their families is tragic.

Some of the histories are startling for what a

different world they seem to take place in.

Others are just as startling for how little has changed. On the one hand, a U.S. Marshall in Western

District, Texas, died because, being a well-raised Victorian gentleman, he assumed

a woman would not lie. On the other

hand, a police officer in the mining town of Gold Hill, Nevada, died as a

result of what is, to this day, the most dangerous situation for a lawman to

get involved in: a domestic dispute. Some of the cases have unexpected elements

that would never occur to a fiction writer, such as the pair of hold-up men who

made their getaways on bicycles.

While many non-fiction books of the old west end

their tale when the lawman dies, this is often just the midway point in Sanders’

telling. He writes about the pursuit,

capture, trial, and punishment of the killers, and the reader will likely be

amazed at how little has changed. We

think of the wild old days as a time when someone uttering, “Get a rope!” was

time for the story to end. In fact, just

like today, legal maneuverings often made these court battles go one for years. Lawyers endlessly debated points such as the

difference between ‘stooped’ and ‘round-shouldered’ in the description of a

suspect. And also like today, the longer

it took to bring the miscreant to justice, the more frequently the press would

start to admire and fawn over the killer, the victims quickly forgotten.

Some of the whims of justice would be laughable if

they weren’t so infuriating. A convicted

murderer and train-robber serving a life sentence turns artist, and sculpts a

bust of the governor, who soon after paroles the killer!

Author J.R. Sanders

Sanders’ subjects are meticulously researched with

primary sources; his bibliography lists numerous newspapers, periodicals, census

and other public records, court transcripts, and books. His style of story-telling is engaging and

accessible, and never dumbed down: hooray for the writer with the courage to

use ‘pettifogging’ when no other word will quite do.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book, and I strongly recommend

it to anyone who wants to learn about the every-day heroics of the lawmen of

the old west.

On Thursday, May 15th, from 7 to 10 p.m.

at William S. Hart Park in Newhall, California, J.R. Sanders will be taking

part in The National Peace Officers Memorial Day. This is a free and open-to-the-public event,

and Sanders will be one of a number of speakers, as well as signing his

book. To learn more, please contact the William S. Hart Museum office at (661)

254-4584 or Bobbi Jean Bell, OutWest, (661) 255-7087.

You can learn more about J.R. Sanders by visiting

his website HERE. You can purchase SOME GAVE ALL from OutWest Boutique

HERE

THAT’S A WRAP!

And that’s all for this week’s Round-up! Have a great Mother's Day!

Happy Trails,

Henry

All Original Contents Copyright May 2014 by Henry C.

Parke – All Rights Reserved

Sunday, January 13, 2013

THE MAN WHO IS MANOLITO!

An Interview with HENRY DARROW

To those of us who grew up in the sixties watching THE HIGH

CHAPARRAL, the actor Henry Darrow and the character of Manolito Montoya are

inseparable. Manolito, with the

infectious laugh, was everything a teenaged boy in the audience wanted to be:

handsome, suave, confidant, smart, competent with fists or firearms, a devil

with ladies – and remarkably lazy! He

was the successful ‘slacker’ long before the term was popularized. Growing up in Puerto Rico and New York , coming to California to act, his big break came when

David Dortort, the creator of BONANZA, decided to do another Western series,

also centered on family. Feeling the

Cartwrights were almost too ideal a family, Dortort decided to create a series

about a dysfunctional family – again, a term which hadn’t yet been coined. And unlike the comparative safety of The

Ponderosa, The High Chaparral was located on the border with Mexico , and on what had been Apache

land, land the Apache would not give up without a fight. The constant sense of danger gave the show a

considerable edge.

With INSP airing episodes on weekdays, weeknights, and

Saturdays, old fans are becoming reacquainted with the show, and a younger

audience raised on Spaghetti Westerns is discovering both its edginess and its

story-telling quality. I recently had

the pleasure and privilege of talking with Henry Darrow about Manolito and his

other roles, including his three different portrayals of Zorro! Every bit as charming and witty as Manolito,

he had me laughing from ‘Hello.’

PARKE: When you were a teenager growing up in Puerto Rico , you wrote a fan letter to Jose Ferrer. Why was he so important to you?

DARROW: Jose Ferrer

was the first Puerto Rican to win an Oscar, for CYRANO DEBERGERAC. When I first competed at University in Puerto Rico , for an acting scholarship, I did some of his

speeches and I copied his voice. And

then I did a little bit of DEATH OF A SALESMAN, playing the older

character. Then I did Mercutio from

ROMEO AND JULIET, and I had fun doing it – it was a good time. And I got to meet Ferrer, and we worked

together in a film, that was in Puerto Rico . It was called ISABEL LE NEGRA (A LIFE OF

SIN), and Isabel, she was a lady who ran a ‘house,’ (brothel) and she donated

hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Catholic Church. And they didn’t bury her on property that

belonged to the church.

PARKE: At what age did you decide to be an actor?

DARROW: I always wanted to be an actor, even as a kid. I remember being in shows, and one of my

first shows, I was a tree-cutter, and another boy played Santa Claus. That was in front of the whole school.

PARKE: You’ve gained your greatest fame playing characters

in western stories – Manolito in HIGH CHAPARRAL, and Zorro and Zorro’s father

in several different productions. Prior

to starring in them, were westerns of particular interest to you?

DARROW: There was a

theatre called ‘Delicious’ -- this was in Puerto Rico ,

and they would charge twenty-five cents.

I would take my brother. The theatre was packed and we’d wind up having

to sit in the front row to see three westerns, and I got to like and understand

Tom Mix, Charlie Starrett – The Durango Kid, Johnny Mack Brown, etcetera. And The Cisco Kid – Gilbert Roland.

PARKE: Oh, he was the

best.

Darrow with Gilbert Roland

DARROW: Yeah, I

really liked him, and he….I don’t know what it was about him. He bought all his films, so you’ll see films

about Cisco Kid with Duncan Renaldo, Cesar Romero, but you won’t see any of

Gilbert Roland. When I played Manolito I

copied one of his bits, which was he was taking a shot of tequila, and he was

with a girl, and he gave her a taste, and then he turned the glass, and took a

taste from where she had been drinking.

And so I thought, ‘I could do that.’

So I tried it, but unfortunately I had a beer mug, and it just didn’t

work. The director said, “What the Hell

are you doing?” I said, “I saw Gilbert

Roland do this, and he did it with a shot glass.” He said, “Henry, you look like you’re

drunk.” So that came to a quick

ending.

PARKE: When you came to California , you joined the Pasadena

Playhouse, where so many great actors got their start.

DARROW: I picked California ;

I found out that the Pasadena Playhouse was about sixteen to seventeen miles

from (Los Angeles ),

actually. I got to work in lots of

plays, and do lots of scenes, and there were many classes, and I really got a

chance to expand – ten or fifteen scenes a year, a couple of plays. I’d work with the second year students and do

plays with them, and it was an important experience for me. Eventually that became the criteria for the

Pasadena Playhouse, that we hit our marks; we overacted a little bit (laughs),

so we had to be careful,

PARKE: Your first feature Western was the very eerie CURSE

OF THE UNDEAD (1959) with Eric Fleming, later of RAWHIDE, and Michael

Pate. Any memories of either man?

DARROW: Eric Fleming

and I, we played chess. And he was a

very good player. Michael Pate played a

Dracula character, and I played his brother.

And that was my first (screen) kiss.

I kiss the girl, and (laughs) by coincidence, my first death scene,

because that was Michael Pate’s girlfriend, and he came and killed me. I don’t remember Michael Pate too well, other

than he was Australian, with the accent.

PARKE: Before your breakthrough with HIGH CHAPARRAL you did

several other classic Western series: WAGON TRAIN, GUNSMOKE and BONANZA. Any particular memories of those shows, and

the characters you played?

DARROW: In WAGON TRAIN I had two lines. Ward Bond took my

one of my lines! It was like, “Giddyap,”

getting the wagon going. And I said,

“Hey, that’s my line!” And the whole set

got quiet. It was like ‘What?’

And he turned and looked at me, and I said, “Well, yeah, you took my

line, and I only have two.” I didn’t

know. So the next day the production

manager comes up to me and says, “You have an extra line with the wagon.” I guess he was shocked too, that I called him

on it. But I did get my extra line. And in GUNSMOKE I did about three separate

episodes. One was a killer, one was a

hangman – I played a Hispanic in that.

And I couldn’t bring myself to hang the guy, but he tried to get out,

people tried to free him, and he got killed in the process. I worked on the show CIMARRON CITY

PARKE: How tall are

you?

DARROW: (laughs) I used to be six feet, but now I’m

five-ten. You lose height and

flexibility.

PARKE: When and why did you change your name from Enrique

Delgado to Henry Darrow?

DARROW: ‘Delgado’ did Latins. I had an agent named Carlos Alvarado and he

only got scripts that had Latin parts.

During the sixties and seventies there were lots of Latin parts floating

around, and that’s all I ever did. I played

a non-Latin once, in a TV show with

Victor Jory, and the character’s name was Blackie; that was it.

PARKE: Let me ask you

about Victor Jory, one of my absolute favorite villains.

DARROW: Oh God, he

was wonderful to work with. But I was a

smug little son-of-a-bitch. He gave a

speech at the Playhouse, and I thought, “Oh God, what’s he talking about?” But he talked about everything that ever

happened, later, for me; to do character work, to continue to work, and never

turn down a job – work everything, do everything. He was one of the guest stars on HIGH

CHAPARRAL, one of the first episodes, with Barbara Hershey.

PARKE: How did you come to David Dortort’s attention? How did you win the role of Manolito Montoya?

Darrow, Leif Erickson, Linda Cristal, Cameron Mitchell

DARROW: Dortort had already created the successful BONANZA,

and then came HIGH CHAPARRAL. And

CHAPARRAL had to do with two families.

Back in the sixties, the casting people used to see plays, and producers

would see plays, so it was a good start for me.

David Dortort saw me in a play, THE WONDERFUL ICE CREAM SUIT, by Ray

Bradbury, in a theatre called The Coronet, in West

Hollywood , on La Cienega. I

then left and did a year of repertory at the Pasadena Playhouse. I was no longer a student. I had been around town for a while, and I’d

given myself five years. And then I gave

myself another set of five years, and I was currently working on my third set

of five years, to stick it out. It was

then that I changed me name from Delgado to Darrow. I looked through the phone book, and there

weren’t that many Darrows, and so my agent at the time, Les Miller and I we came

up with Henry Darrow.

PARKE: I understand

that, looking for you under the wrong name, it took Dortort months to find

you. What did you think when he finally

tracked you down?

DARROW: Dortort asked me, what do you think about

Manolito? They sent me the script, and

all of a sudden I’m doing another Latin!

I just changed my name!

PARKE: How was David

Dortort’s vision for CHAPARRAL different from the many Western series that came

before?

DARROW: He came up

with this concept. The Civil War had

just ended. We had the Mexican family of high esteem south of the border, and

then we had the Tucson

family, the (socially lower) Cannons.

And the man who played my father, Frank Silvera, negotiated a romance

between his daughter, Linda Cristal and the old man, John Cannon. Dortort had such an affinity for Latin

actors, and he used us. On BONANZA he

hired many. He hired almost every Latin

that I had ever known of. He hired them

as Federales and bad guys, one after another, and they all played on CHAPARRAL,

about a hundred-odd people a year. And

he had Ricardo Montalban on twice, and Alejandro Rey came on, and there was

Fernando Lamas and there was Barbara Luna – there were a number of other people

that he brought into the show.

He made the character of Manolito a sort of a wastrel, and

Linda Cristal as my sister, oh, she was just incredible. She was wonderful to work with; she was the

only other one who spoke Spanish, so if we were short in a scene, ten or fifteen

seconds, they would say, “You guys get into an argument.” Go “Ayyy, Manolito!” “Ahh ,

Victoria Europe .

PARKE: Were you an

experienced horseman before the show?

DARROW: My experience

as a horseman – I think I was about eleven, and I got on a horse in Central Park , and it ran away with me (laughs). (For HIGH CHAPARRAL) they taught me how to ride a horse in the

sand, in the Valley, someplace.

PARKE: I was 13 when

HIGH CHAPARRAL started, and I loved it.

Your Manolito and Cameron Mitchell’s Uncle Buck, ‘The Loose Cannon’,

were my favorite characters by far.

DARROW: Cameron

Mitchell was like what you call him, ‘The Loose Cannon,’ that’s certainly like

him. He loved gambling, and he loved his

pitchers of Margarita, and we’d drive down to the dogs, at Tubac, near Tucson . I was on a film directed by Cam

where one of the stars that had guest-starred on our show, Rocky Tarkington, played

a Christ-like figure, and I think it was finished, but it was held up in the

courts. Luckily I got my money up front.

(laughs) And working with Cameron

Mitchell – we wound up doing an episode called FRIENDS AND PARTNERS, where we

bought a little ranch that had some silver on it. We thought we were conning the owner about

getting the silver out of the ground. He

said, “Well, if you did that, if you do this, if you do whatever, it’s gonna

cost you guys a lot of time and work to get that silver out of the

ground.” That’s when we looked at each

other and, ‘What? He knows about the silver mine?’

PARKE: What memories

do you have of the other cast members?

Was Leif Erickson as stern as he seemed?

DARROW: Leif Erickson

was pretty good. He was a straight-shooter. He helped me invest some moneys in Hawaii . I remember, with Leif Erickson I was always up

and around, and here we are, working on location in 105, 110 degree heat. I had gotten woolen pants, I had a suede

jacket, a heavy black hat, and Leif Ericson would say, “You’re just up too

much. It’s not good for you, not good

for your health. You should sit

down.” So I started to sit down a little

more, and he said, “You know what? I

think you should lie down. Go into your

air-conditioned dressing room and lie down.”

So I learned fast, going into the second year, to sit down, lie down,

and it worked out okay. And I got a

chance to work with a lot of actors, TV actors who had been around, like Jack

Lord, Bob Lansing, Steve Forrest, Victor Jory like I mentioned, Barbara Hershey

– it was good. I had a good time.

Mark Slade, Blue, he eventually was written out. He asked to be let go because of a film he

wanted to do; he was going to do a film with Willie Nelson, and then it fell

through. The ranch hands, the buddies,

were Don Collier, and Bobby Hoy, who recently died. And there was Roberto Contreras, died, Ken

Markland died, Jerry Summers died, Roberto Acosta died. We used to have get-togethers and go to the

western shows. Don Collier would say to

me (deeply), “Well Henry, you’ll be doing what I’m doing, and

blah-blah-blah-blah. You’ll do rodeos

and…” And I said, “No, I’m a serious

actor; I don’t do that crap.”

(laughs) And he taught me how to

do some shooting, and then there’s a drum-beat, and somebody with a pin – Pop!

-- the balloon pops. (laughs) I did

everything he said that I would do.

PARKE: Speaking of

actors who you’ve worked with, what was Barbara Luna like?

DARROW: Oh, she’s a

funny lady, a funny lady. She has so

much energy – I worked with her in soaps, too.

She once came up to me in a restaurant – she was with Michael Douglas –

and she said, “Michael’s with some people from Sweden , and they know you. And he wants to know why.” Well, they saw HIGH

CHAPARRAL.

PARKE: What were your favorite episodes?

DARROW: One with Donna Baccala; she played a love

interest. It was a good show, and she

unfortunately died in my arms. Favorite

directors? Billy Claxton. He was the best – he did more episodes than

anyone else.

PARKE: In the late

1960s, there was great pressure to tone down the violence on television. Did that have a good or bad effect on the

show?

DARROW: There was

great pressure to tone down violence, and we did. And in some instances it brought out different

patterns of my character. We didn’t

shoot; you couldn’t point a gun. That

became a little weary, because if you pulled your gun out of the holster you

had to aim it at somebody. So you just

took the gun out and held it across your lap, and c’mon, that’s not right!

PARKE: It goes

against everything western, the idea that you don’t pull your gun unless you

intend to use it.

DARROW: We had one

producer, his name was Jimmy Schmerer, and we had a great fight scene. All the Indians in the world were down in the

valley, they were shooting, and people were getting shot, and then he panned

around, and there wasn’t one body – not one body! The network said, ‘What the Hell is going

on?’ And he said, ‘You told us we were

not allowed to shoot anybody and kill them.’

And what you saw was six or eight shots of people getting shot in the

shoulder, going down, getting up, somebody got shot in the leg; somebody helps

him get on a horse.

PARKE: After four seasons and 97 episodes, HIGH CHAPARRAL

was cancelled. Did you know it was

coming?

DARROW: I read it in Variety – that’s how I found out. That really hurt, oh man did that hurt. We used to win the first half-hour, opposite

THE BRADY BUNCH, when we were on Fridays.

And then (ABC) added another show, THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY. And once they added that show, we were

done. Even though we had Gilbert Roland

coming on next season as a regular. I

had a good run; I had a beautiful run.

(But after) CHAPARRAL, people sort of stayed away from me because I was

so tagged as Manolito, that character, that they didn’t hire me right

away. But then all of a sudden, someone

on MISSION :

IMPOSSIBLE hired me, nine months, ten months into the year, and that changed

the whole outlook. I then got a lot of

guest shots, I did HARRY O, and then I did a number of other series.

PARKE: Would it be

indelicate to ask about the residual situation on CHAPARRAL?

DARROW: Well, we came

in right when they changed the ruling, that you could show the episode ten

times, and you’d get paid ten times. And

then all of a sudden you wouldn’t get paid anything. And they’re showing it hundreds of hours

around the world, and I just think of the people who did THE LONE RANGER, and

they don’t get piss. They got

nothing. I thought, well, at least did

it, and they had a buyout of some kind, say two hundred bucks, three hundred

bucks an episode, and it was worth it; it was worth the anxiety.

PARKE: I understand

you went to Sweden

after HIGH CHAPARRAL ended.

DARROW: I had talked

with Michael Landon because he had done a show in Sweden , and made a lot of

money. And I thought, what the Hell, I

can do that. And he did a couple of

fight scenes for the people. So I wound

up singing some songs, and using whips.

I did about twelve shows in Sweden . I sang in Swedish. I first started in my regular Manolito

wardrobe, and then the second half of the show was ‘Henry Darrow Sings,’ in

modern clothing, and the people were talking while I was performing! As the producer said, “You’ve gotta put on

the outfit! They don’t know Henry

Darrow, they know Manolito. So if you

don’t wear your outfit, they won’t know who the Hell you are.” And I started to find out. I’d call the kitchen and say, “This is Henry

Darrow; we’ve got no service.” He said,

“No, tell them you’re Manolito,” and then they were there – bam!

I was the second most famous man in Sweden . The King was first and I was next. I was in

this helicopter, and they put me down near the water, and there was a band

starting to form together, and I asked, “When do they start playing my

theme?” And they said, “They’re not;

they’re waiting for the King.”

(laughs) They asked me to leave,

and that was the end of that. There was

one Mexican restaurant in Sweden ,

in Stockholm ,

and we went to it, and they had elk tacos!

It was fun, and that lasted for a while. I lost about eight or ten

pounds.

PARKE: You’ve gone on

to do many movies, plays, TV series like HARRY O and THE NEW DICK VAN DYKE

SHOW, but apart from Manolito, the character you’re most identified with is

Zorro! Culturally, what is the

significance of your playing Zorro?

DARROW: I was the first Latino to play Zorro. And I think

that I am the only actor who has been in three productions of Zorro. I was in the animated series, and then I was

in ZORRO AND SON, where I played the over-the-hill Zorro, and then I played

Zorro’s father in Spain

in several different productions, and I replaced Efrem Zimbalist Jr.

PARKE: Didn’t you

actually audition for the Disney ZORRO series back in the 1950s? What role were you up for?

DARROW: I had read

for the part of a heavy in ZORRO back in the fifties, with Guy Williams. And I actually wore Guy Williams’ wardrobe in

ZORRO AND SON in 1983, except they had to take it up three inches, because he

was three inches taller than I was.

PARKE: You first played Zorro in the Filmation cartoon

series in 1981. What was it like doing

cartoon voices?

DARROW: It was

different, because you don’t work with anybody.

You just work by yourself. They

lock you in; you do your stuff. And I

remember Lou Scheimer said, “CBS says you’re a little suggestive.” I said, “Like what?” “Like senoriiitah. Buenos noches.”

“I have to give it a little something.” He said, “No, no. It’s got to be straight.” So it became (monotone) ‘senorita, buenos

noches.’ With no inflection; that’s

exactly what they want. So now I listen

to the animated series, that’s why it sounds so flat, monotone and one-note. I replaced Fernando Lamas. I don’t think he did any; I filled in for him

before he even started. I was going to

be not-cast, when I started with the inflection.

PARKE: Did you work

with Don Diamond, who played Sergeant Garcia?

DARROW: No, I never

did. He may have played on CHAPARRAL,

but I don’t remember. He was a funny

man, did voices –

PARKE: Played Crazy

Cat on F-TROOP.

DARROW: That was

good.

PARKE: It’s funny

because he was one of those guys, who were so identified as a certain kind of

Hispanic character, and of course he wasn’t, but he did nothing but that for

decades.

DARROW: I know, and

that was the funny part of it. And of

course it was the same with Bill Dana; Jose Jimenez.

PARKE: With whom you did ZORRO AND SON.

Zorro and Son

DARROW: Yes, in

1983. We had a short-lived series, ZORRO

AND SON. It was unfortunate that the

pilot was one of the first episodes, and one of the best episodes was the last

one. Where Greg Sierra puts on an outfit

like Zorro, and takes over my house, and chops up my furniture with a sword. And I chopped up my furniture, because it

annoyed me that he was cutting my furniture the wrong way. I said, “No -- yah!” And I slammed down and

cut a chair in half. Anyway the episode

ended, we were both in the cantina, I say, “I’ll pay for this.” And he says, “No, I will.” And I said, “No, no, no senor, por

favor.” And he said, “No you

won’t.” And the episode ended with both

of us arm-wrestling to see who would pay for the drink. And it was fun working with him, and it was

fun working with Bill Dana (as Bernardo); it was delicious. It was a good five episodes that we did, and

unfortunately the last one was the best.

And I showed the pilot to a wonderful producer, Garry Marshall. And he said, “Henry, if they concentrate on

you and your son and play that relationship, that’ll work. But if they’re going to make fun of Zorro, I

don’t think it’s going to last long.”

And that is exactly what happened.

The writers didn’t know what to do with it, if it was a half-hour

cartoon show for the kids, for Saturday morning. We did have a little heavy-build scene here

and there. But they never decided what

kind of a comedy it was. (At the end of

an episode) there was a beautiful girl, and he kissed the girl, and I got to

hug the priest. Then both of us were on

our horses, and I turn to him and say, “Next time I kiss the girl and you hug

the Padre.” (laughs) Some of it was comedic, and it worked, but

other stuff didn’t. It’s like you’d say,

“The walls have ears,” and – BAM! – they’d cut to plastic ears on a wall. Oh man!

It was just too corny. But Bill

Dana was a delight to work with. And he

wrote a lot of his own dialogue – he came up with lines.

PARKE: He wrote for

Steve Allen. If you can write for Steve

Allen you can do anything.

DARROW: That’s

right!

PARKE: In 1990 you went to Spain to star as Zorro’s father in

the New World ZORRO series for four seasons, and over sixty episodes. How did you enjoy the experience?

In the New World ZORRO

DARROW: That was a

delight. Duncan Regeher was just

delightful. He was the most thorough

actor I ever worked with. He got up at

four o’clock and worked for an hour with his weights, with his stretching, with

his yoga. He was incredible. And Michael Tylo, his Alcalde was like

Iago. He was threatened. And then the guy that replaced him was John

Hertzler, and he made him a little more of a braggart.

PARKE: I just watched

the TV movie cut from the episodes where you don’t know that you have a second

son – great fun, great stuff!

DARROW: Oh my gosh!

That was a good show. And that

guy (James Horan, who played the second son) voted for me – part of my Emmy win

for SANTA BARBARA

was from doing the soaps with him. He

had seen some other shows that I had done, and he said, “That’s it! That’s it!”

PARKE: In 2001 you

starred on stage in THAT CERTAIN CERVANTES.

How did this project come about?

DARROW: Harry Cason

was a waiter when I lived in Pasadena ,

California

PARKE: We’ve got a

friend in common. Morgan Woodward was

the lead villain in SPEEDTRAP, the first movie I ever wrote.

DARROW: Morgan was a

delight, just a delight. And he did the

most GUNSMOKES in the world. He got us

together, my wife and I. His ex-wife had

a theatre in Midlands, Texas ,

a dinner theater. And I played THE

RAINMAKER, and I had a ball. We had a

good, good cast; we played it for a month, and it was great, I mean working in Texas was really

something. One of the lines that I

liked, that they said about themselves was, “Hank, if you lose your dog, you

can see your dog get lost for three days.” (laughs) Then we went to a party,

and Holy Cow, we drove for hours, and it was just land – land and the wind and

dust and tumbleweeds rolling around. I

got a chance to do a lot of things because of CHAPARRAL, thank goodness.

PARKE: Why did you

and your wife, Lauren, relocate to South

Carolina ?

DARROW: Because my

hair had gotten white. I was looking

older, and all of a sudden, there I was competing for one and two and three

lines. When I’d go to a reading, there

were guys who had done series like I had.

We all looked at each other and said, ‘What the Hell are we doing

here?” Here we are for three lines; for

two lines. We’ve got all the credits in

the world, and the guys that are hiring us are in their late 20s, their early

30s, and it was like, ‘What have you done?’

Oh man, to have to start all over again.

I just couldn’t, I couldn’t hack it.

So we had a friend who was doing a series on the Kentucky Derby, and she

talked to us about Screen Gems being here, and a lot of theatre being done at

the University, etcetera, so we chose here, came and bought an old two-story

Carolina house, with a little bit of land – nothing great, just a large

backyard. We got into cats, and the all

of a sudden we got into the real estate game.

But we got into the real estate game just before the bottom dropped out,

so we’re stuck with about eight houses.

PARKE: Do you ever

get back to Los Angeles ?

DARROW: I went to the

Gene Autry Museum

PARKE: I recently got

over to Old Tucson Studios, and it’s nice to see that there is still so much

standing from HIGH CHAPARRAL.

DARROW: Yes; I’m

supposed to go there in March, for the 41st reunion. And this will be my last visit, because it’s

just too strenuous for me. Well, that’s

the way it is.

PARKE: Do you know

who else is attending?

DARROW: The only two

are alive are Rudy Ramos, who plays Wind, and Don Collier.

PARKE: Would you do another Western if you were offered the

right script?

DARROW: I’m doing a series on Daniel Boone, a five-parter on

PBS. I told the producer I can’t

memorize anymore. She said, “Can you

read cue-cards?” I said yes, she said,

“You’re hired.” They hired me as the

Cuban tavern owner. So I’ve got a job

coming up some time next year. And it’s

nice to get back into it. And on

occasion I’ve done some movies for film students at the University. 8, 9, 10-minute films. Because I go down there and I coach and I

teach, and I go to talks. So I still

keep my hand in it as best I can.

BOOK REVIEW -- HENRY DARROW – LIGHTNING IN THE

BOTTLE by Jan Pippins and Henry Darrow, is the delightful biography of the

actor we all discovered as Manolito Montoya on THE HIGH CHAPARRAL. Of course, his life is so much more than that,

and his childhood in Puerto Rico and New

York

For fans of CHAPARRAL, Jan

Pippins’ meticulously detailed telling of the history of the show, from concept

to casting, from the rise to the demise, is a compelling book within a

book. But there is another dimension to

this story as well. As a white guy

watching Westerns in the sixties, I hadn’t a clue of the great significance, to

a sizable minority of our population, of having Latin characters who were not banditos

or servants or Federales, but people

of equal or higher wealth and social standing than the whites. Throughout the book the testimonials to

Darrow’s importance to the careers of so many Latino actors, sometimes by

example, sometimes by personal involvement, is as moving as it is

unexpected.

Darrow’s career did not end with

CHAPARRAL, and the stories about his TV, film and stage work are enlightening,

amusing, and sometimes are cautionary tales, as are some elements of his

personal life. HENRY DARROW – LIGHTNING

IN THE BOTTLE is a book that will be heartily enjoyed by fans of the man, of

the show, and documents through him a unique and significant time in the

history of American entertainment. I

highly recommend it.

‘DJANGOMANIA’ SWEEPS THE NATION!

Even as weepy-whiners call for a

ban on DJANGO UNCHAINED action figures, fearing small children will be

encouraged to play ‘slave and master’ games, Tarantino’s Western continues to

entertain. His own theatre, the New Beverly

Cinema Hollywood

That's about all for tonight! Sunday night's Golden Globes were good for Westerns -- Best Actor for Kevin Costner in HATFIELDS & MCCOYS, Best Screenplay for Quentin Tarantino for DJANGO UNCHAINED, Best Supporting Actor for Christoph Waltz for DJANGO, and Best Actor for Daniel Day-Lewis in LINCOLN.

Next week, in time for Hallmark Movie Channel's GOODNIGHT FOR JUSTICE 3: QUEEN OF HEARTS, the best film yet in the series, I'll have a review, plus interviews with Luke Perry and Ricky Schroder. Have a great week!

Happy Trails,

Henry

All Original Contents Copyright January 2013 by Henry C. Parke -- All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)