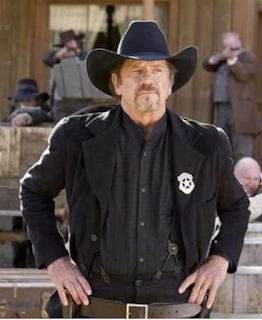

TOM WOPAT – NOT JUST A GOOD OL’ BOY

TOM WOPAT ON HIS INSP ‘COUNTY LINE’ MOVIES, BEING LUKE DUKE, HIS

WESTERNS, AND MUSICALS

By Henry C. Parke

On Monday, November 28th,

at 10 p.m. Eastern time, the second of INSP’s County Line movies

starring Tom Wopat, County Line: All In, will play on INSP. It’s also streaming on Vudu, and is available

to purchase on Amazon.

No disrespect to Waylon

Jennings, there’s nothing wrong with being a good ol’ boy, but fans who know Tom

Wopat by his portrayal of rural characters in movies like County Line

and series like The Dukes of Hazzard may be surprised to learn

that he’s also a major Broadway musical star. Tom certainly has his country

credentials, growing up in Lodi, Wisconsin, “On a farm. Every other farmer had a little dairy farm.” But his goals would soon draw him beyond his

state’s border, and he credits Wisconsin’s education system for preparing him.

TOM WOPAT: Back in the sixties. you remember when

Kennedy said we we're going to the moon in nine years? We did, you know. I think that our schools in

Wisconsin were exceptional, in that decade especially. And I was fortunate

enough to have really fine music teachers, even when I was a little kid. The local music teacher kind of took me under

her wing and encouraged me to learn songs and do solos. And then a guy from

North Carolina came to the University of Wisconsin, and he, again, took me

under his wing and taught me. I sang opera, I sang German Lieder art songs. I

had a really wonderful musical education in our little high school.

HENRY PARKE: So you were

first attracted to music, rather than acting?

TOM WOPAT: Definitely. I

did my first musical when I was 12. I

kinda learned acting just in self-defense (laugh). I started getting better and

better parts and, when I went to the University, (I did) West Side Story,

and Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar -- I played Judas in

that. It was amazing. And also there were guys that, again, took me under their

wing. I was directed towards the summer stock theater in Michigan, where I

could get my [theatre actors’ union] Equity card. After I got my Equity card, I

took my ‘68 Chevy and 500 bucks and two guitars and drove to New York.

When I got to New York,

it was pretty quick. I got there in the fall of ‘77, and by the spring of 78 I

was in an off-Broadway musical. I left that one to go to D.C., where I played

the lead character in The Robber Bride Room, the Bob Waldman musical. I

left that to go back to Broadway and replace Jim Naughton in I Love My Wife.

So within six or seven months of being in New York, I was on Broadway in the

leading role.

HENRY PARKE: When you

were doing so well on Broadway, why did you go to Hollywood?

TOM WOPAT: To quote Larry

Gatlin, they made me an offer I couldn't understand (laugh). It was shortly

after I finished an off-Broadway run in Oklahoma. I read for Dukes,

and that afternoon they called and said, you want to fly to LA and do a screen

test? I said, I guess so. I don't know (laugh), I'm just a farm boy from

Wisconsin. So I packed up a few things in a paper bag and got on a plane. And

10 days later, we were shooting in Georgia.

I mean, I went from Wisconsin in the fall of '77 to New York, and was on

Broadway in the summer of 78. And in the fall of 78 we were making the Dukes

of Hazzard.

HENRY PARKE: That's

amazingly fast.

TOM WOPAT: Yeah, it was a

bit of a whirlwind. When I found out I got the part, I was more frightened than

relieved. I had just put my toes into the water in New York City, doing

Broadway, and then all of a sudden I gotta go and do a role in an action

series. I had no idea how to approach television. It's a different ballgame

than being on stage. But I figured I'd

make a little money and go back to Broadway, but not so: Dukes was a big

hit immediately. So then I moved to LA for a few years.

HENRY PARKE: You mentioned going to Georgia to shoot. I

thought the series was shot at Warner Brothers in Burbank.

TOM WOPAT: We shot five shows in Georgia, and it was a

little grittier, a little more adult show than what it ended up being. They

started preaching to the choir a little bit. And some of the scripts got fairly

cartoonish for a while. We even had a visitor from outer space in one episode (laugh),

which is really bizarre.

HENRY PARKE: How did you get along with John

Schneider?

TOM WOPAT: I’ve got six brothers, but I count John as

number seven. I really, really enjoyed

my time. I enjoyed our cast. Our cast was very close and still is, really a

nice bunch of people.

HENRY PARKE: You worked

with two of my favorite actors in that regularly, Denver Pyle as Uncle Jesse,

and James Best as Sheriff Rosco Coltrane.

TOM WOPAT: Terrific actors,

terrific. And Sorrell Booke [Boss Hogg] might have been the best of the bunch. Denver and Jimmy probably had more

visibility, but Sorrel was kind of ubiquitous for a while. He's in What's

Up, Doc? He was on M.A.S.H. And he was a really, really talented

guy. All three of them were very talented and very helpful to the younger crew.

HENRY PARKE: Why did you and John Schneider famously walk

out?

TOM WOPAT: Well, they [the

Dukes producers] sell all the dolls and the cars and all that

merchandise stuff, and we were supposed to get a pretty good taste of that. But the way they did it is they had a series

of shell companies. So they would buy

the company that made the toys, they would buy the company that licensed

everything. They were making half a billion dollars a year, and we were getting

a check for a couple of grand. So we thought we were being cheated. And

unfortunately, that's the word we used in our lawsuit, and they took umbrage to

that and then sued us. In retrospect, it might not have been the best bunch of

decisions that we made. However, it was the first time that two stars of a show

had walked out together, and that meant something to other actors in the

business. We didn't really get a raise

(laugh). They just dropped all the lawsuits. And we did get a couple of new

writers, and I was able to direct a half a dozen episodes. I very much enjoyed

that. We had a little more control of

the artistic input into the show. I mean, that could be an oxymoron for Dukes

of Hazzard, but John and me, we had a lot of skin in the game. We were out

there every week doing this stuff, and they kept shortening the shooting

schedule. And they wanted to use

miniature cars and barns and stuff. They were doing stunts that weren't stunts,

filming stuff with toys and presenting it like it was real. And that was kind

of an insult. So, for one of my last episodes, I took out all the miniature

stunts that they were gonna do, and I put in footage from earlier shows, different

angles of jumps and crashes that we did that weren't used. We had this huge backlog of stuff like that,

and I put it to good use. And John got to direct; John directed the final one. In

retrospect, we may have shortened the life of the show a little bit with our

walkout, but you know, hindsight's 20-20. We moved on and had a lot of success.

I started making records, and from 1991 until 2013, I was probably in a dozen

different shows on Broadway.

HENRY PARKE: Including your first historical Western role,

as Frank Butler in Annie Get Your Gun.

TOM WOPAT: We had so much fun! Bernadette Peters is the perfect leading

lady, and I worked with her for almost two years. That's really the high point of my Broadway

career. Then Glengarry Glenn Ross opened up a

whole different territory of parts to me. People were not aware that I had any

range. They're used to seeing me as the big dog in a musical. And in Glengarry,

I was the patsy, I was the one who got taken advantage of. That was interesting;

that was hard. Because I'm so used to playing the hero. Playing

somebody that gets skunked, it's not a feeling I wanna walk around with all day

(laugh), but I've had other interesting parts. I did a thing with Cicely Tyson,

The Trip to Bountiful. That's the last time I was on Broadway.

HENRY PARKE: And you played Sky Masterson in Guys and

Dolls.

TOM WOPAT: Oh man, what a

dream cast. Nathan Lane was Nathan Detroit, Faith Prince was Miss Adelaide,

Josie de Guzman was Sister Sarah. One of

my favorite parts is playing Billy Flynn in Chicago, because he shows up

late and leaves early, and he wears one outfit.

HENRY PARKE: In 2010 you did the film Jonah Hex, which

is certainly an edgy Western --somewhere between historical and steampunk.

TOM WOPAT: It's like, metaphysical. I read for it and they decided I could wear a dental prosthesis and (laugh) pull it off. That was kind of a complicated situation. I think they went through three directors getting that thing filmed. We worked in Louisiana. I enjoyed it. It wasn't the most fun I've had; I'll tell you the most fun I’ve had doing a Western was Django Unchained. Oh my gosh. That was great. Basically, my part [as a U.S. Marshall] is kind of a one- trick-pony, but what I did in the movie is exactly what I did in the audition. Tarantino was very, very gracious. People don't know, but Tarantino used to study acting with James Best. [Tarantino] would take a bus up from Torrance, and he would have a class on Thursday night, and then Jim would let him sleep in the classroom. Then he would come over to Warner Brothers the next day, I think he's 18, 19 years old, and hang out on the set being one of Jim's guests. So now he has a habit of using TV stars in his films; like Don Johnson was so super in Django. I enjoyed Longmire, another Western. I'm playing kind of a villain in a sense. It's always implied that I'm taking money from the oil companies to let them do what they want in my county. That was a quality organization. And one of the producers was the daughter of one of the people that worked on Dukes at Warner Brothers.

HENRY PARKE: You shot Django at Melody Ranch.

TOM WOPAT: Right, the Gene Autry place.

HENRY PARKE: As a singer, did you feel any Gene Autry

vibes there?

TOM WOPAT: No. But you feel the vibes of his horse

that's buried there standing up -- you know that? He buried Champion standing up. We had a good

time. One notable thing that Tarantino does is, when you go to the set, you

check your phone. There's no cell phones on the set. Which I thought was genius, and it's not

brain surgery to do that. You want

everybody focused on what they're supposed to be doing, not checking their

email.

HENRY PARKE: Right. And

there's way too much of that on sets these days.

TOM WOPAT: When I was doing A Catered Affair one

time, there was a kid down in the front row and he was looking at a cell phone

and I was like six feet away. I'm

sitting at a table right at the edge of the stage and I just looked down there

and I just shook my head back and forth and he put the phone away.

HENRY PARKE: I was surprised to realize that the first County

Line movie you made for INSP was four years ago.

TOM WOPAT: Yeah, it was a

while back, and it was actually their first action movie. Their previous movies

had largely been romcoms, maybe with a little bit of drama to them. Ours was the first action one. I had so much

fun. I had such a great time. And then, they asked if I wanted to do two more, two

sequels back-to-back. I said, yeah, you bet. So we filmed them down in

Charlotte and around there. And again, a lot of fun, the most fun, really, I've

had since Django or Dukes. Because in these shows I'm kind of

the big dog, the leader of the pack and I enjoy being able to set the tone on

the set, and making sure everybody has a good time. So I take the cast and crew

out bowling, or I'll bring in a big pot of chili that everybody has to have a

taste of, or make ribs for everybody. I enjoy that kind of hosting situation, and

being the alpha male. It's not probably

the most attractive thing to be the alpha male, but (laugh) I enjoy it.

HENRY PARKE: And you need

one.

TOM WOPAT: Usually

there's a leader on the set. When we were doing Dukes, the leader on our

set was a director of photography, Jack Whitman, may he rest in peace. He set

the tone. He had come from shooting Hawaii 5-0, so him and his crew had

all come from Hawaii. And there was a certain vibe on the set that was focused

but gentle. And erudite. He was a real leader in a very soft-spoken way. He was

a good guy to learn from.

HENRY PARKE: For folks

who haven’t seen the first County Line movie, and don’t know your

character, Sheriff Alden Rockwell, what does the title refer to?

TOM WOPAT: There’s a café, basically a diner, that sits on

the county line, on the road. There's a

line that runs down the middle of the café, a line drawn across the table

exactly where the county line is, so if I have a beer, I have to put it in the

other county, because we don't drink in my county. There was cooperation between me and the

sheriff in the next county [Clint Thorne, played by Jeff Fahey], and we had

actually served together in Vietnam as Marines, so we’re heavily bonded.

HENRY PARKE: I don’t want to give away too much, because

it’s a good mystery as well as a rural crime story.

TOM WOPAT: It's a little bit like Walking Tall.

HENRY PARKE: Yes. Alden Rockwell became a widower in the

first film. And the diner’s

proprietress, Maddie Hall, is played by Patricia Richardson.

TOM WOPAT: And Pat Richardson has a really nice quality.

It gives you a sense of comfort to see somebody that you know and recognize. I

mean, being kind of my girlfriend and also running a diner and looking after my

health, there's a comforting part of that. I think one of the real attractions

of Dukes to families is that it's about family, and it's about taking

care of your family, and making sure that nobody comes to harm. And when we're

talking family, we talk extended family. So if Boss or Rosco got their tail in

a crack somewhere, Jesse would make sure that we helped them out of it. I liken

it to The Andy Griffith Show.

HENRY PARKE: Oh, I can see that immediately. In the County

Line films Abby Butler plays your daughter, and it’s a very interesting and

very unusual relationship between you two, with her as a recently returned Iraq

War vet.

TOM WOPAT: Well, she's a

pistol, man! She didn't take any guff off me. I'm proud of her for joining the

service, but I'm frightened for her at the same time.

HENRY PARKE: Right.

TOM WOPAT: There's that one scene in the original County

Line where we're out on the porch and breaking down pistols that we've just

taken from a bunch of nefarious dudes. And I asked the director, I said keep

this in a two-shot. Because it really works, and any cuts back and forth would

be more of a distraction than a help. If you look at old movies, a lot of the

really good scenes are shot in a two shot.

They let you decide who you want to watch for the reactions and who you

want to listen to. It's not like [single close-up] ‘talking heads’, which

television in the eighties got into a lot. We had a lot of fun making County

Line and we had just as much fun making these two new movies.

HENRY PARKE: Someone who’s new to the mix is Kelsey Crane,

who plays Jo Porter, who is now the sheriff across the county line.

TOM WOPAT: She's terrific. She's got a lot of talent and

she also has the moxie to know how to work a set and how to let people do their

jobs without getting in their stuff. Cause a lot of actors will kind of try to

be the center of attention all the time. And that gets pretty old.

HENRY PARKE: If there are going to be more County Line

movies, or possibly a series, the determining factor will probably be how

audiences relate to your character. Why

do you think viewers will keep coming back?

TOM WOPAT: Because Alden is the kind of a guy who, if he

sees an injustice, he's gonna try and do something to make it right. Whether he

really has the power to do that, the agency to do that, that doesn't matter.

He's going to do what he can, legally, mostly.

THE PERFECT GIFT FOR THE

MOVIE-HISTORY LOVER:

VITAGRAPH – AMERICA’S

FIRST GREAT MOTION PICTURE STUDIO

BY ANDREW A. ERISH

ARTICLE BY HENRY C. PARKE

NOTE: The videos you’ll

see embedded throughout the article are not merely clips, they are complete

films, some running just three minutes, others nearly half an hour.

While most film

biographers and historians set out to teach you more about the films and personalities

you’ve already grown to love, educator, historian and author Andrew Erish has

set himself a more ambitious task: he seeks out the film pioneers who have been

undeservedly written out of the histories.

The depth and detail of his research is astonishing, and his prose is

accessible and entertaining. With his

previous tome, the fascinating Col. William N. Selig, the Man Who Invented

Hollywood, he told of the life and work of a film pioneer whose name

belongs alongside D.W. Griffith, Jesse Lasky, and Cecil B. DeMille. He wants to save Vitagraph from the same sort

of obscurity.

The output of this

initially Brooklyn-based movie studio was remarkable. “They were leading the way,” Erish explains. “From 1905 on, they were producing more movies

than anyone else in America. They were the first to consistently release a film

a week; then it became two films a week until, by 1911 or 1912, they were

releasing six shorts and one feature every week. It's just an astounding output,

and covering every kind of movie imaginable.”

The men who formed

Vitagraph were unlike any of the other movie moguls. Sam Goldwyn was a glove salesman. Louis Mayer

was a nickelodeon theatre operator. They all came to movies from business. But not Vitagraph’s J. Stuart Blackton and

Albert E. Smith. “They started out as vaudeville

entertainers.” Both English immigrants,

who arrived in America at the age of ten, Smith was a magician, ventriloquist,

and impressionist. Blackton was a cartoonist

and quick-sketch artist. “They

understood the aesthetic that ruled vaudeville, which was a variety of

entertainment that would appeal to the widest possible audience, with something

for every segment of the audience. And understanding firsthand what audiences

reacted to, as stage performers, they had insight that really no mogul coming

after them had; they had experience.”

Erish makes a convincing

case that Blackton created the first animated films. “There's absolutely no doubt about it,” he

asserts. “A lot of history books mistakenly credit, a Frenchman named Emile Cohl,

but Cohl's first animated film was made after Blackton had already made four or

five. And Cohl's very first film is actually aping a film which Blackton had

made a year earlier.”

Below is Blackton’s wonderful

1907 film, The Haunted Hotel.

The Haunted Hotel – 1907 dir.

Blackton

While Blackton was

pioneering animation, “Smith, on the other hand, was very interested in making

action-oriented films, and great with moving camera ideas and staging dramatic

moments and action to their greatest effect, in real locations, so that these

stories would appear more real. And if he was staging something at a steel

mill, he would photograph at real steel plants, and put real steel workers

mixed in with his lead actors, and it all looked real.”

They excelled in

Westerns, eventually. “The very first Westerns Vitagraph made were in Prospect

Park in Brooklyn. And they're really bad, there’s just no getting around it. But

they had a great story guy named Rollin Sturgeon, who they promoted to

director. The guy had such a strong story sense and such a strong visual sense,

and they sent him out to Los Angeles to open up a second studio, primarily to

make Westerns. He made a film about the Oklahoma land rush called How States

are Made. When the starting cannon

is fired, he covers everything in an amazing, extraordinary wide-angle shot

that starts with an empty hill. And you

start to see the crest of the hill is covered in these little dots. Then they start to move down the hill and you

realize these are people on horseback, covered wagons, the horse-buggies --

they're all coming towards the camera. That shot lasts over three minutes and

it's absolutely stunning to let it play out in real time in a single shot.”

How States are Made -- 1912

While Thomas H. Ince is credited

with “inventing” the Western, and the studio system (and for dying on William Randolph

Hearst’s yacht while sailing with Marion Davies and Charlie Chaplin), his

younger brother Ralph Ince was one of Vitagraph’s finest Western directors. “I

think Ralph Ince is second only to [D.W.] Griffith (for) his contributions to

the language of cinema. In The

Strength of Men, with the two guys shooting the rapids with

no protection, and then fighting in the midst of a real forest fire! It's in

front of your eyes, the way it would be if that dramatic story were really

happening for real.”

The Strength of Men –

Ralph Ince -- 1913

Vitagraph also excelled

in comedies, creating the first great movie comedian with John Bunny, here seen

assisted by fourteen-year-old Moe Howard!

Mr. Bolter’s Infatuation –

John Bunny -- 1912

Another huge comedy star

was cartoonist-turned-actor Larry Semon.

Although his hilarious sight-gag comedies are forgotten in America

today, “Around the world, Larry Semon's movies have been shown, non-stop to

this day on TV in Spain, Germany, throughout South America, and Italy.”

You can watch Semon

perform with a yet-to-team Stan Laurel…

Frauds and Frenzies – Larry Semon, Stan Laurel

--1918

… and Oliver Hardy. If you’re offended by black-face jokes, you

can skip Hardy.

The Show – Larry Semon,

Oliver Hardy – 1922 Norman Taurog

While the story of the demise

of the Vitagraph company is by turns infuriating and heartbreaking – they barely

survived into the sound era -- their influence on film is inestimable. Many of their discoveries went on to notable

careers both in front of and behind the camera.

“Edward Everett Horton made his first movies at Vitagraph, and became a

big silent star. Adolph Menjou started at Vitagraph, playing suave, debonair

characters. Frank Morgan, who played the Wizard of Oz, got his start in

Vitagraph movies, as a much younger man, back in the teens. And Larry Semon hired

a young guy who had directed one or two films, a kid named Norman Taurog, to be

his co-director and co-writer. And Northern Taurog went on to have an

illustrious career. He directed Bing Cosby and Bob Hope, he directed six Martin

and Lewis movies, he directed nine Elvis movies – he was Elvis' favorite

director.”

Vitagraph is

the winner of the 2022 Peter C. Rollins Book Award and received an award from

the Popular Culture Association as one of the best books of 2022. It’s available directly from The University

Press of Kentucky, in hardcover and paperback, here: https://www.kentuckypress.com/9780813195346/vitagraph/

It can also be ordered from

independent bookstores, Barnes and Noble, and Amazon.

I’VE GOT A BOOK

DEAL!!!!!!!!!

I am thrilled to announce

that I am writing a book for TwoDot Publishing!

Tentatively entitled The Greatest Westerns Ever Made, it will feature

many of my articles from True West magazine.

It’s the perfect Christmas gift – but not this Christmas. It will be in book stores in the spring of

2024.

THE INSP ARTICLES

Just about a year ago,

the very fine folks at The INSP Channel, whom I’ve known for a decade, and

written for a little bit, hired me to write a couple of articles about Westerns

for them every month. I’ve been having a

great time doing it, although between writing for them, and being the Film and

Television Editor for True West magazine, I am sure you can understand why The

Round-up has been appearing less frequently than it used to.

One really exciting thing

that has come from this was to chance to interview John Wayne’s son, Ethan, on

camera. I’m including below a link to

that interview, and links to several of my INSP articles enjoy!

ROBERT TAYLOR

https://www.insp.com/blog/robert-taylor-hollywood-star-husband-to-barbara-stanwyck-and-cowboy/

LANA WOOD INTERVIEW

KATHARINE ROSS AND SAM ELLIOT

https://www.insp.com/blog/katharine-ross-and-sam-elliott-marriage-careers/

REDFORD, NEWMAN, AND GEORGE

JOHN WAYNE AND JAMES ARNESS - WHEN THE STARS ALIGN

…AND THAT’S A WRAP!

What better possible way

to follow up my interview with Tom Wopat?

I’ll be talking with John Schneider about Dukes of Hazzard, his

Westerns, and his new movie, To Die For.

Please check out the December 2022 issue of True West, with my article

on the best mountain man movie ever made, Jeremiah Johnson! And if I don’t get to post before the

holidays, have a very merry Christmas, a happy Chanukah, a happy New Year, and

a joyous anything and everything else that you celebrate!

Happy Trails,

Henry

All Original Content

Copyright November, 2022 by Henry C. Parke – All Rights Reserved